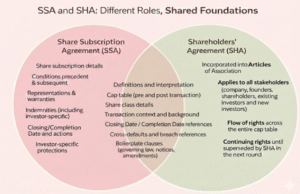

In investment transactions, the Share Subscription Agreement (SSA) and the Shareholders’ Agreement (SHA) are referred to as transaction or definitive documents. While they serve distinct purposes and operate on different planes, they are closely linked. Understanding how they differ, where they overlap, and how they interact is essential for clarity in both execution and long-term governance.

The SSA is entered into between the company, founders, and investors (often individually) to record the details of the subscription. It captures the economics and mechanics of the investment, including inter alia:

- Number and class of shares being issued

- Share price

- Share subscription amount (consideration)

- Conditions precedent, for example:

- Private placement offer (PAS-4)

- Special resolution for issuance and allotment of shares

- Closing Date (remittance of funds)

- Conditions subsequent, for example:

- Allotment of shares (PAS-3)

- Issuance of shares in dematerialised form

- Representations and warranties

- Indemnity provisions, including survival periods

- Pre-closing and post-closing actions (largely operational in nature)

While many obligations under the SSA culminate at closing, certain provisions, particularly indemnities and fundamental warranties, can and often do survive the transaction. In fact, fundamental warranties are typically uncapped by time.

The SSA can also differ between investors. Depending on the nature of the investment, an investor may require additional representations from the founders, a different indemnity construct, or specific protections tailored to its risk assessment. In such cases, investors usually enter into separate SSAs rather than a single combined SSA with all incoming investors.

The SHA, on the other hand, is a governance document. It is executed amongst all the stakeholders, i.e.

- the shareholders, including existing investors,

- incoming investors,

- founders, and

- the company.

Its objective is to define shareholder rights and obligations in the context of the complete cap table.

This includes

- voting rights,

- board composition,

- reserved matters,

- transfer restrictions,

- exit mechanisms,

- information rights, and

- other protective provisions that govern how –

- control and

- economics flows among stakeholders over time.

There is, inevitably, overlap between the SSA and the SHA. Definitions, boilerplate clauses, transaction details such as issue price and number of shares, and the cap table often appear in both documents.

However, despite this overlap, the SSA and SHA serve intrinsically different purposes.

From a legal standpoint, the SSA is purely contractual. The SHA, however, derives additional legal strength because its rights and obligations are incorporated into the Articles of Association.

By virtue of this incorporation, the SHA attains a higher level of legal enforceability.

In the event of any inconsistency between the SHA and the SSA, the SHA typically prevails.

In practice, however, both documents are usually drafted in parallel, with care taken to align common provisions and avoid conflicts altogether. This is where cross-referencing becomes particularly important.

A common example is the definition of the “Closing Date” or “Completion Date”.

The SHA often states that this term shall have the meaning ascribed to it in the SSA.

This matters because multiple rights, timelines, and consequences under the SHA are triggered with reference to that date.

It is also important to note that the Closing Date may differ for different investors, depending on their respective SSAs.

Termination provisions provide another illustration.

An SHA may state that it will automatically terminate if closing is not consummated on the Closing Date in accordance with the SSA. In such a case, the SHA entered into amongst all stakeholders will terminate only with re

spect to the particular investor whose closing has not occurred.

Similarly, definitions of breach or “Cause” under the SHA often encompass events set out in the SSA. The two documents therefore operate as a connected framework rather than in isolation.

In effect, the SHA continues for as long as a person remains a shareholder in the company, until it is superseded by a new SHA in a subsequent round.

Where there is no change in the rights structure in a later round, a new investor can simply execute a Deed of Adherence to the existing SHA, thereby agreeing to be bound by it as it stands. A Deed of Adherence, however, is not executed for an SSA.

A fresh SSA is typically entered into for each round or investor because the SSA records round- and investor-specific economics that cannot be rolled forward through adherence. Subscription amounts, pricing, conditions precedent, representations and warranties, and indemnity constructs are all specific to that investment and are therefore agreed afresh.

A single document: SSHA?

It is not uncommon to see a single combined document, often referred to as an SSHA, particularly at an early stage. This is usually driven by a smaller number of stakeholders, minimal differentiation in rights among investors, or practical considerations of time and cost. As the company and its investor base evolve, however, the separation between SSA and SHA tends to become both necessary and useful.

Key takeaway

Taken together, the SSA governs how capital comes in, while the SHA governs how rights flow thereafter. They are distinct, but not independent. When drafted thoughtfully and read together, they form a coherent contractual framework that supports transactional certainty at entry and disciplined governance over the life of the company.

Author,

Mansi Handa