I joined Auxano as an analyst just about two months ago, and I recently had the chance to sit in on my first in-person founder meeting. Until now, my exposure has largely been focused on pitch decks and data. Meeting a founder face-to-face in their office, hearing the full arc of their journey, and watching the dynamic of investor-founder discussions was an entirely fresh experience.

The Story Behind the Business

The founder spent over an hour walking us through their journey, from their early days of experimenting with one facility to scaling into a pan-India operation with multiple verticals. The depth of industry insight stood out to me, giving me a window into a space I had never explored in detail before. Meeting the founder in their office added a personal dimension, making their passion and deep knowledge of the sector even more tangible.

The Investor Lens

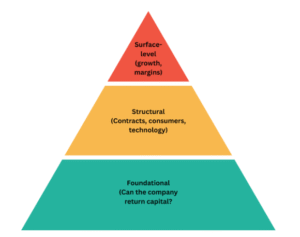

As much as I was absorbing the founder’s story, I found myself equally focused on the questions my senior colleague asked. They weren’t surface-level queries but deeper, structural ones about the contracts and customers, the technology, and the infrastructure.

It was an important reminder that venture investing isn’t just about celebrating growth but testing whether the foundations of that growth are truly strong and sustainable.

Why the SHA Matters

A focal point of the conversation that surprised me was a debate around the Shareholders’ Agreement (SHA). Before this meeting, I thought of the SHA as legal housekeeping, but watching the discussion unfold helped me realise how critical these terms are. They define governance, responsibilities, and long-term alignment between founders and investors. A small difference in their interpretation could have lasting implications.

I recalled an Auxano blog on overlooked SHA clauses and, for the first time, saw those abstract points become a crucial part of the meeting. As we wrapped up that discussion, it became clear to me that documents like the SHA aren’t separate from investment analysis but part of the same bigger question: how strong and reliable is the foundation on which this business, and our potential partnership, really rests?

Post-Meeting Reflections

After the meeting, we discussed the business from a different lens, and the tone shifted from story to scrutiny. It wasn’t about the founder’s vision anymore it was:

- Could this business actually return capital?

- Could any risk sink it entirely?

- Would I invest my own money, and if yes, how much?

I realised this is where all the moving parts, the founder’s qualities, the industry dynamics, the descriptive metrics, come together. You don’t look at them in isolation; you combine them into one fundamental question: can this company make money, and in what timeframe? That framing changed how I saw the conversation.

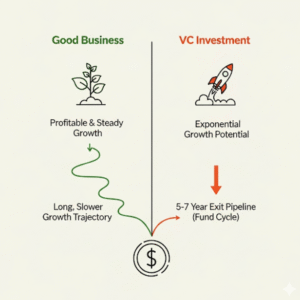

I began to appreciate the difference in the nature of returns a VC expects. While most businesses might deliver predictable annual returns of 12–15%, the venture capital model targets a much higher 30–50% XIRR to compensate for high risk and illiquidity.

Ultimately, the relationship between founders and investors is built on the premise that the upside has to be large enough to justify the risk we take.

Another layer that stood out was the importance of exits. I had always thought of a “good business” as one that was profitable and growing steadily. But with venture financing, it isn’t enough for a company to succeed eventually, its trajectory also has to fit into the fund’s exit pipeline. With a 5-7 year fund horizon, exits can’t be endlessly delayed.

Even if the business might generate strong returns in the long run, the timing and structure of those returns matter. It’s crucial to ask when and how we will be able to realise value. That perspective made me understand why the post-meeting debate leaned so heavily on not just if the company would generate financial returns, but when and how it would translate into an actual exit for us as investors.

Takeaways for Me

Walking out of that meeting, I felt like I had a crash course in what it means to sit at the table as an investor. I didn’t just learn about that company – I glimpsed into the venture process itself: a three-part rhythm of listening, questioning, and resisting shortcuts.

Here are the lessons I’m carrying forward:

- Listen for lived experience, not just metrics: The founder’s journey enriched the numbers.

- Ask deeply, not just technically: Growth means little if the foundations don’t hold.

- Treat documents like dynamics: An SHA isn’t paperwork—it’s potential tension and alignment in print.

- Always view through the exit lens: A company can be strong and profitable, but unless its trajectory fits the fund’s exit pipeline, it may not be the right investment.

That first meeting was more than a company briefing, but a masterclass in narrative, analysis, and negotiation. And as I look ahead, I’m tuning my senses to listen beyond slides, to question beyond presentations, and to know that in the little details often lies the big picture.

Author

Ragini Ramanujam